How can mechanisms supercharge your teacher education practice?

Share this page

Date published 24 March 2023

Teacher Education Fellows is a cutting-edge and collaborative programme for teacher educators who want to help teachers get better in their settings. On it, you can hone your ability to design and deliver great professional development by translating the latest theory into practice.

Programme lead Nick Pointer is a former science teacher, experienced instructional coach, and previously led on our Instructional Coaching programme pilot. On Teacher Education Fellows, Nick and our current Fellows are grappling with the big questions of teacher education by exploring the latest theories in the field.

Here, Nick explores the challenges faced when translating the theory of ‘mechanisms’ in teacher education into practice. He shares some practical advice that teacher educators can use to develop their expertise in designing and delivering professional development.

The recent Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) Guidance Report on Effective Professional Development (2021) represents a sea change in our understanding of teacher education. Not only does it seek to isolate the underpinning active ingredients (‘mechanisms’) with a causal link to pupil outcomes, but it also finds that the more of these that are present, the greater the impact of professional development (PD).

However, one challenge that teacher educators face is the job of translating these mechanisms into practice. I’ve experienced several conversations with school leaders that have run along the following lines:

“We’re using the mechanisms to make our PD more rigorous and have decided to link teachers’ progress in instructional coaching to their appraisal. This is aligned with the Setting Goals mechanism from the report.”

or

“I know that we should add more mechanisms into our PD to make it more effective, but I’m not sure what good looks like. How would Manage Cognitive Load look in practice without adding more time into sessions?”

In the first case there is a risk of misinterpreting the purposes of certain mechanisms. In the second, there is a lack of clarity around how new mechanisms might be incorporated into existing approaches.

The overarching question is: How can the mechanisms of effective professional development be efficiently translated into practice to have the greatest impact?

What are the EEF mechanisms and how are they categorised?

The EEF report outlines 14 mechanisms that have a causal impact on student learning. The mechanisms are grouped into four categories that represent the overarching purposes of professional development.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Keeping the purpose of each mechanism in mind when planning PD is a powerful approach to interpreting the mechanisms in a way that is faithful to the research, whilst considering the need to contextualise to individual settings.

One key mechanism that can be challenging to translate into practice is Setting Goals.

Translating the mechanisms into practice: Setting Goals

The purpose of goal setting within PD is to motivate teachers (see Figure 1). Goals help direct and manage teachers’ attention towards desirable new practices. This can support teachers to attend to and track their emerging competence, and thereby stay committed to the changes they are making (Locke and Latham, 1990).

Non-example of high-quality translation

One pitfall of Setting Goals is linking it to high-stakes accountability systems within schools:

Goal setting should help teachers to manage and direct their own attention. Since here the goal is externally imposed on the teacher, it is likely to undermine their agency and motivation for ongoing development (Worth & Van den Brande, 2020).

In addition, linking staff development to judgments of their effectiveness could further reduce their motivation as it risks framing PD as a high-stakes, accountability-based process.

How might we improve this in practice?

Consider the following alternative approaches:

Since the underlying purpose of this mechanism is to catalyse teachers’ motivation, the first example above is likely to help manage teachers’ attention and support them to focus on a specific and manageable aspect of classroom practice.

The ‘supercharged’ example is even more powerful. Not only does it make the change manageable, but it also reminds the teacher why they are doing it. Directing teachers’ attention to how a new approach aligns with their existing classroom goals can help them to better integrate it into their existing practices, sustaining and building their motivation.

Translating the mechanisms into practice: Monitoring and Feedback

Another key mechanism is Monitoring and Feedback. Feedback links to the previous mechanism of Setting Goals – it’s not always clear to us how successfully we’re achieving a goal, or what we need to change to be more successful.

The purpose of monitoring and feedback within PD is to help teachers to develop new practices (see Figure 1) by supporting them to focus on how they might close the gap between where they are now and where they’d like to be.

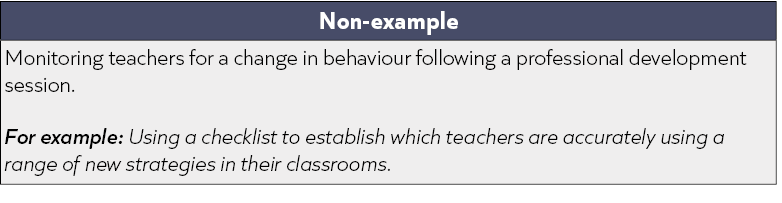

Non-example of high-quality translation

One pitfall of Monitoring and Feedback is linking it to attempts to monitor and evaluate the quality of teachers’ practices in schools:

This process is summative in nature, rather than formative. This raises the stakes and makes teachers less willing to show vulnerability and share challenges.

Attempts to turn PD (which should be inherently developmental) into an evaluative exercise are misguided and even can have a negative impact on teachers’ practices. Teachers may instead focus on trying to prove they are meeting the school’s expectations, rather than reflecting on how to improve their implementation of new approaches in practice.

How might we improve this in practice?

Consider the following alternative approaches:

Rather than assuming that teachers will immediately be able to effectively implement a new technique in their classrooms, the first example above focuses on using feedback to help teachers develop over time. This is much more likely to lead to effective implementation and a virtuous cycle of improvement and motivation for teachers.

This effect can be ‘supercharged’ when we focus on the reasons for using a strategy. This approach reinforces the importance of teacher agency mentioned above – the teacher should be deciding when and why to use a new strategy in their classroom. This will discourage the teacher from using the strategy indiscriminately ‘because they’ve been told to’. It also makes it more likely that teachers will improve in their ability to apply new approaches into their classrooms.

The road ahead for teacher educators

Teacher educators have the challenging job of translating these mechanisms into their contexts, whilst maintaining fidelity to the underpinning theory. By considering the purposes that the mechanisms are trying to serve in professional development, we are more likely to ensure that these are not being distorted in implementation.

This is the kind of work that is at the heart of the Teacher Education Fellows programme, where we engage with cutting-edge research into professional development, reflect on current practices, and refine them to improve teacher education nationwide.

References

Worth, J., & Van den Brande, J. (2020) ‘Teacher autonomy: how does it relate to job satisfaction and retention?’ Slough: NFER.

EEF (2021) Effective Professional Development: Guidance Report. London: Education Endowment Foundation. Available from: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/guidance-reports/effective-professional-development

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990) A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance. NJ: Prentice Hall.